Disclaimer*: The articles shared under 'Your Voice' section are sent to us by contributors and we neither confirm nor deny the authenticity of any facts stated below. Parhlo News will not be liable for any false, inaccurate, inappropriate or incomplete information presented on the website. Read our disclaimer.

This post is also available in: العربية (Arabic) اردو (Urdu)

I am not the most religious person on the planet, in the country, in my state, or my city. In fact, it’s very likely that I’m not even the most religious person in my little neighborhood. Yet for some reason, a big part of my cultural identity is inseparable from the Islamic religion.

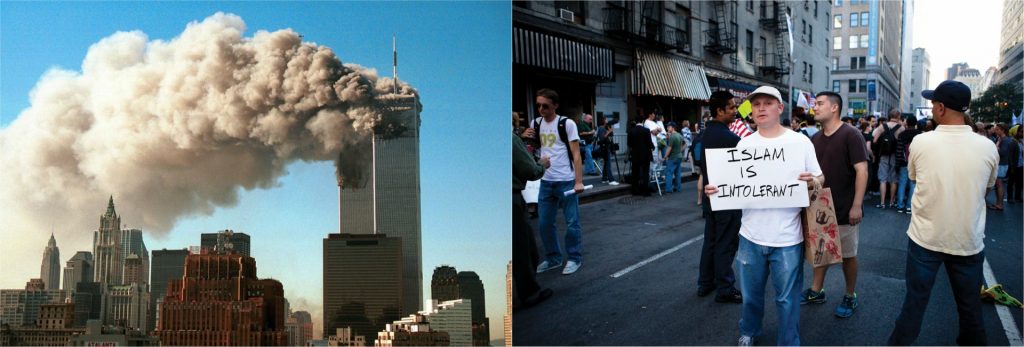

I was born and raised in America and I was brought up as a Muslim in the most traditional sense. I was taught to read the Quran at a young age by my mother, I was taught how to pray and instructed to do it five times a day, I was taught why we fast during the month of Ramadan and encouraged to do the same myself if I felt able to, etc. And then when I was six years old, 9/11 happened. Suddenly, I began to witness firsthand a wave of hatred that nobody around me was able to understand or explain, and it is a hatred that has persisted ever since. In many ways, it’s gotten worse.

A common occurrence growing up, and even now, is having people, (usually white people), coming up and accusing my “evil book” of commanding me to do something that’ll lead to the destruction of good old American values. In the early days of Islamophobia in America, it seemed like such a thing was relegated to isolated incidents out on the streets, in classrooms, etc. Public spaces where small arguments were taking place, instances where fear mongering, ignorance, and hate took the place of actual research and education.

As I’ve grown older, however, I’ve noticed that this line of arguing has made a place for itself within the realms of discourse. It’s got books, podcasts, T.V. shows, and perhaps most dangerous of them all, politics devoted to it. Out of context passages taken from the Quran, translated into English, and presented as a broken mural that makes it seem like every Muslim on the planet believes in an Islamic world order.

It doesn’t matter if we were born here or not, if we’ve never shown signs of aggression, these people are convinced that the Quran tells us to wipe out the “infidels”, and they are convinced that the word “infidel” means them. Other trigger words such as, “jihad” and “sharia” are used liberally, words that most of the non-Muslim people who use them are ignorant of the actual meaning of.

About a year ago, right around the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election, I saw an article circulating covering a Muslim family that was going around their neighborhood to introduce themselves to their neighbors and tells them a little bit about Islam to put them at ease. To show them that they were just regular people who were not out to harm anyone. This type of action has been subtly encouraged by a few feel-good films (ex: ‘My Name is Khan’) in the past nearly two decades.

If we just show them that we’re good, that we’re not like the ones they see on the news, they’ll love us! They’ll understand us, protect us, maybe even emulate us. With all due respect to that family, it’s not that simple, and in many ways, such an action is incredibly dangerous and borders on flat-out stupidity.

I am all for promoting acceptance through education about the things we don’t understand for all people and, regarding Islam specifically, if someone asks you a question about the religion or if someone is presenting false information as fact, you should answer the question or refute the false information with the truth. Or, if you yourself don’t know enough to provide an accurate answer but do know where the person can find accurate information, refer them to a valid source. But Muslims do not owe anyone an explanation for why they should be allowed to exist. There is no group on Earth that should have to justify their race or religion for the satisfaction of others. It should highlight just how dangerous a place we’re in if people have started selling their neighbors on why they should be allowed to simply exist.

I’ve deviated from my main talking point, which is people spreading misinformation about Islam to justify their own hatred. As I’ve gotten older, I’ve noticed that when it comes to situations like this, the general response most Muslims have is a denial of Islam being a violent religion. They say it’s a religion of peace, that compassion and tolerance are at the root of the religion, and they’re right. However, the people who quote violent passages from the Quran, they aren’t wrong about those passages being in the Quran, to begin with. Yes, they take them out of context. Yes, knowing those few passages does nothing to inform them of the religion or most of its practitioners’. But those people still hang onto those small pieces of a much bigger picture and attempt to use them against us.

This is where it becomes incredibly important to hang onto those religious roots. In my own experience, learning about Islam myself came not as a spiritual process necessarily, but one that I saw as a requirement to be able to respond to ignorance with proper, educated responses. It won’t do for me to simply say that the religion promotes peace, I see being able to point out what it says in detail while simultaneously acknowledging the more violent parts with proper context as a necessity. Even if someone whose roots lie within an Islamic country isn’t religious themselves, part of their cultural identity is still defined by those roots.

In America, we have made that reality ourselves. It’s easy for people with privilege to claim they don’t see race or religion and that such things are simply social constructs, but that’s not a solution. For the average person who isn’t afforded that privilege, differences in race and religion are a very real thing. In a perfect world, people wouldn’t call me a terrorist because of my brown skin and thick beard, but that’s not the reality of things. Hateful people see these differences and create the divides themselves, so that even people who aren’t religious, who may not identify with their Pakistani, Afghan, Iraqi, Yemeni, etc. roots any more than white Americans identify with their European ones, still suffer from the same profiling and hate-fueled attacks that the rest of us do.

I feel compelled to embrace my roots not only because I want to, but because certain divides that were firmly established in the post 9/11 climate have forced me to. It’s a matter of identity if I can hang on to what the truth is about the things that make up my cultural identity, then bigots can’t take it away from me. And they certainly can’t ever use it against me. I didn’t always have a beard, I’ve certainly never had an accent, I don’t walk around with a prayer cap on my head, (there’s nothing wrong with any of that), but my skin has always been the color that it is.

My name has always been one that has its roots in Islam, and because of those things I’ve always stood out in the eyes of non-Muslims, particularly white Americans. And I haven’t been spared from Islamophobic attacks for those reasons. There’s no point in ignoring certain parts of myself because those people certainly won’t.

No matter what I do, no matter where I was born, where I was educated, etc. I’ll never be able to separate myself from my roots, not anymore. Maybe I could’ve twenty years ago, but things are different now. One of the best ways that I’ve found to combat ignorance and hate is to entirely embrace every aspect of my cultural identity. The Pakistani roots, the mixed American education, and upbringing, the Islamic background, all of it. If I know my history, I can tell others about it, and most importantly, I can keep it alive during times when it’s incredibly difficult to do so.